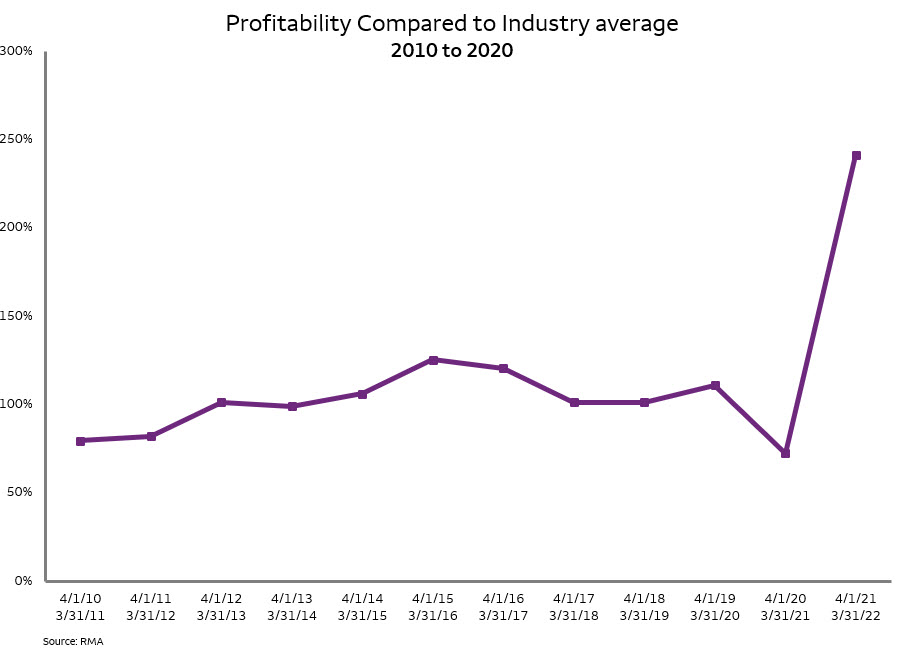

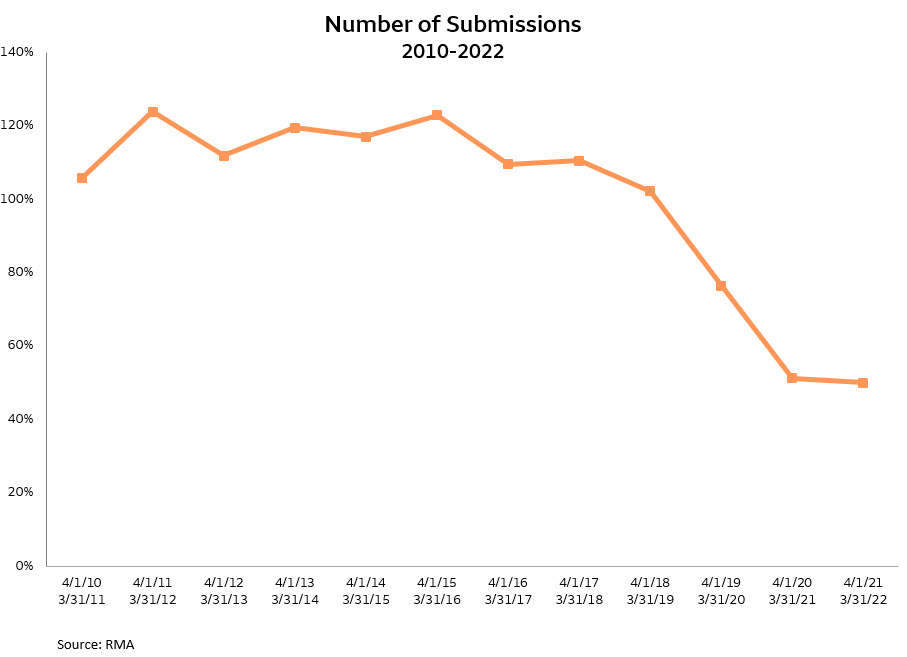

The calm after the storm offers a lot of opportunities assuming one was not wiped out by the storm. Let’s call it the survivor’s dividend. According to the Risk Management Association’s (RMA’s) recently released data, and depicted in the chart below, the restaurant sector’s profitability hit a record high in 2021. The RMA database, which looks at thousands of restaurant financial submissions, saw profitability skyrocket to almost two and half times the previous 10-year average. At the same time, the number of submissions declined by more than 50% from the pre-COVID number. Many restaurants did not survive the COVID bust in order to be able to enjoy the post-COVID boom, and there are indications that 2021’s record profitability has already reverted to more normal profitability.

The calm after the storm offers a lot of opportunities assuming one was not wiped out by the storm. Let’s call it the survivor’s dividend. According to the Risk Management Association’s (RMA’s) recently released data, and depicted in the chart below, the restaurant sector’s profitability hit a record high in 2021. The RMA database, which looks at thousands of restaurant financial submissions, saw profitability skyrocket to almost two and half times the previous 10-year average. At the same time, the number of submissions declined by more than 50% from the pre-COVID number. Many restaurants did not survive the COVID bust in order to be able to enjoy the post-COVID boom, and there are indications that 2021’s record profitability has already reverted to more normal profitability.

So why the record profits? And, why the reversion to more normal profits?

One of the biggest questions around the profitability data involves the accounting for Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans. For some smaller restaurants, the record spike in profitability could almost entirely be traced to the infusion of funds from the forgiveness of (PPP) loans. According to an article in Restaurant Business Online, as of February 2021, the restaurant sector had received more than $18 billion in PPP loans.1 No doubt, with the additional COVID support programs that followed, even more money flowed into the industry, thus helping them survive. As many a farmer will tell you, the margin on a government disaster payment is hard to beat.

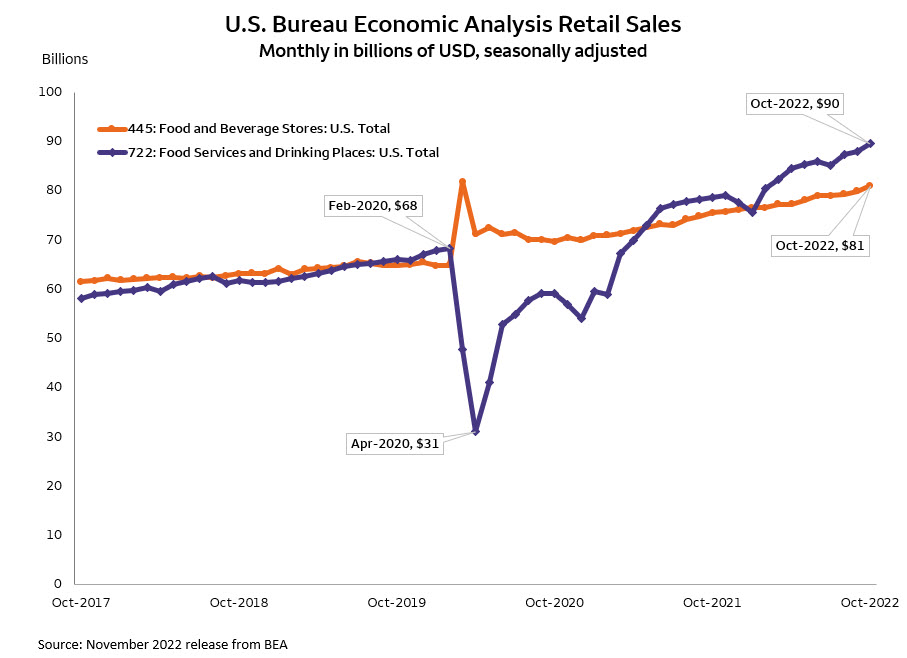

Those restaurants that did survive were able to tap into the amazing resurgence in spending on food away from home (FAFH) as U.S. consumers looked for the variety and convenience that restaurants provide. The Census Bureau’s Advance Retail Sales data series shows this boom. Monthly food service and drinking place spending crashed from $68 billion in February 2020 to $31 billion in April 2020, but since that nadir, spending has raced to a new record of $90 billion in October 2022. This represents a 32% increase in spending for FAFH. Much of this increase reflects the food inflation for the FAFH category that has jumped by 18% since February 2020, but there has been a substantial increase in the spending on restaurants even taking the food inflation into account.

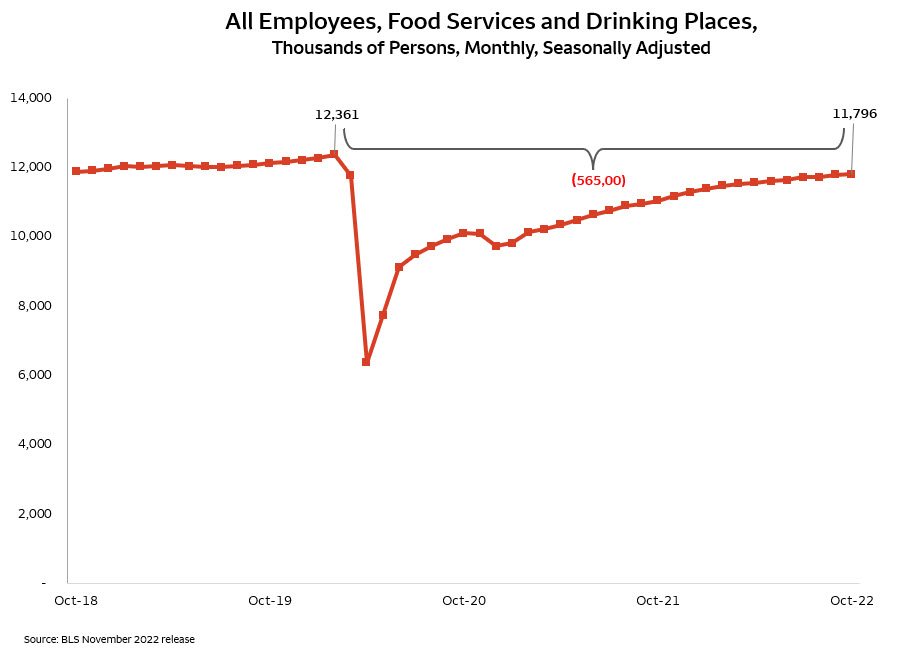

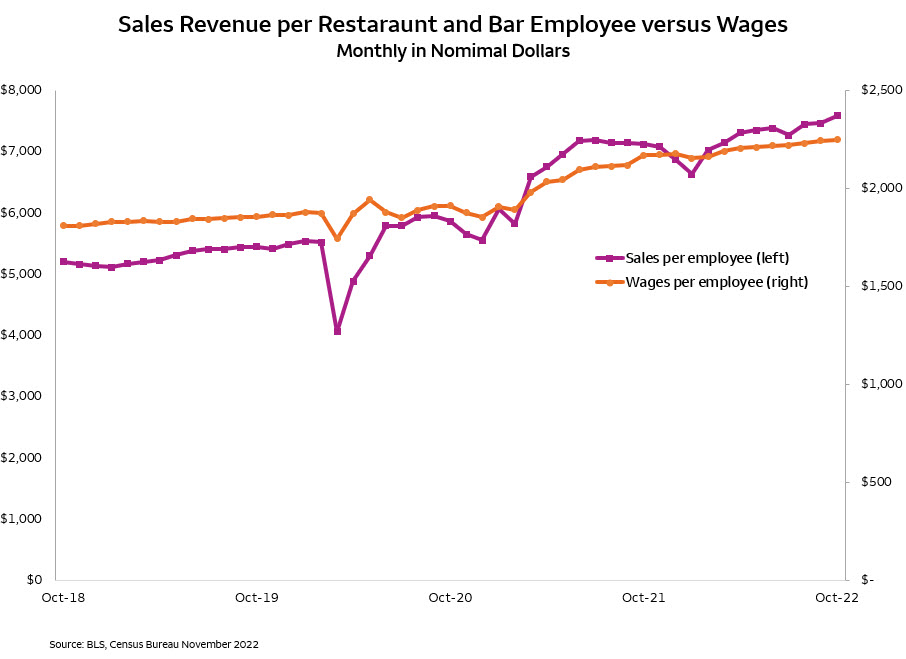

At the same time, the restaurant sector continues to struggle to keep restaurants staffed. The most recent Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) payroll report shows that the sector remains 565,000 employees below its pre-COVID peak. Overall payroll has exceeded the pre-COVID peak by almost 800,000 employees. This represents 1.4 million additional employees deciding to work somewhere other than within the restaurants and food services industry. It appears that the restaurant sector has decided to work with the new labor arrangement to increase profitability. While the restaurant sector has increased the average weekly wages by 20% cumulatively since February 2020,2 sales per employee have increased by 37%.

The rate of wage increases in the restaurant sector has slowed noticeably in the last couple of months. October 2022’s increase was 3.6% on a year-over-year basis, which slightly exceeds the average from the previous decade. While we often hear from our restaurant borrowers that they would like to see more job applications and stability, the industry has stopped pushing up wages which is often counterproductive. While higher wages don’t attract new applicants, they do encourage existing employees to go across the street for a raise.

So, what will set the tone in 2023 for restaurants?

Above-average profitability and strong consumer spending for FAFH will drive increased investment. The investment will focus on throughput capacity that doesn’t require large amounts of staffing growth. Menu engineering will continue to limit choices to improve throughput and reduce ingredient complexity, and restaurants will push the labor onto the food manufacturers who can do more automation and achieve economies of scale. Margin compression should ease as food ingredient price inflation slows and restaurants continue to hike prices faster than what consumers realize with food at home (FAH). Lastly, the number of restaurants should grow as the new entrants work to fill openings left by the shutdowns that came from the COVID bust.

1 Restaurantbusinessonline.com; Restaurants and hotels draw $18B in PPP loans, the highest for any industry

2 Bureau of Labor Statistics, November 2022

Michael Swanson, Ph.D. is Wells Fargo’s Chief Agricultural Economist. Based in Minneapolis, his responsibilities include analyzing the impact of energy on agriculture and strategic analysis for key agricultural commodities and livestock sectors. His focus includes the systems analysis of consumer food demand and its linkage to agribusiness. Additionally, he helps develop credit and risk strategies for Wells Fargo’s customers, and performs macroeconomic and international analysis on agricultural production and agribusiness.

Michael Swanson, Ph.D. is Wells Fargo’s Chief Agricultural Economist. Based in Minneapolis, his responsibilities include analyzing the impact of energy on agriculture and strategic analysis for key agricultural commodities and livestock sectors. His focus includes the systems analysis of consumer food demand and its linkage to agribusiness. Additionally, he helps develop credit and risk strategies for Wells Fargo’s customers, and performs macroeconomic and international analysis on agricultural production and agribusiness.

Michael joined Wells Fargo in 2000 as a senior economist. Prior, he worked for Land O’ Lakes and supervised a portion of the supply chain for dairy products, including scheduling the production, warehousing, and distribution of more than 400 million pounds of cheese annually, and also supervised sales forecasting. Before Land O’Lakes, Michael worked for Cargill’s Colombian subsidiary, Cargill Cafetera de Manizales S.A., with responsibility for grain imports and value-added sales to feed producers and flour millers. Michael started his career as a transportation analyst with Burlington Northern Railway.

Michael received undergraduate degrees in economics and business administration from the University of St. Thomas, and both his master’s and doctorate degrees in agricultural and applied economics from the University of Minnesota.

1122-00309